- Home

- Aimee Pogson

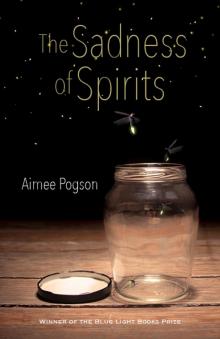

The Sadness of Spirits

The Sadness of Spirits Read online

the sadness of spirits

BLUE LIGHT BOOKS

The Artstars

Anne Elliott

What My Last Man Did

Andrea Lewis

Girl with Death Mask

Jennifer Givhan

Fierce Pretty Things

Tom Howard

The Sadness

of Spirits

stories

Aimee Pogson

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

INDIANA REVIEW

BLUE LIGHT BOOKS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Indiana Review

Bloomington, Indiana

© 2020 by Aimee Pogson

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-05045-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-05046-5 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 25 24 23 22 21 20

Versions of these stories have been published in the following journals: “Unnatural” in the Berkeley Fiction Review, “Red Ballooning” in Juked, “Oh, Dr. Brown” in PANK, “The Long Man” in Western Humanities Review, “Uncle Rumpelstiltskin Will Teach You to Dance” in Chautauqua, “The Sadness of Spirits” in SmokeLong Quarterly, and “These Clouds, These Trees, These Fish of the Sea” (as “Cooking for the Emotionally Repressed”) in Nimrod.

For Kevin, Every Day

contents

acknowledgments

Unnatural

Red Ballooning

Oh, Dr. Brown

The Invisible Boy

Aching in the Grass

These Clouds, These Trees, These Fish of the Sea

Dolls

The Long Man

Disappearance

Mailman Fantasies

Winter

The Sadness of Spirits

Uncle Rumpelstiltskin Will Teach You to Dance

The Key Maker and His Kin

acknowledgments

It would be impossible to list all of the people who supported me in the creation of this book, but I will do my very best.

First, thank you to the Indiana Review staff for seeing the potential in my work and being willing to give it a chance. I’m grateful that my first book found such a great home.

Thank you to the many people who have helped this book along its journey at Indiana University Press. In particular, thank you to Ashley Runyon, Anna Francis, and Leigh McLennon for their insight and their patience with my many questions.

Thank you to my fellow MFA students Dustin Hoffman, Brandon Jennings, Angela Purdy, Joe Celizic, Brad Modlin, and Megan Ayers for their feedback and friendship. Our conversations both in and out of the classroom have stayed with me for all these years.

Thank you to my professors at Bowling Green State University: Lawrence Coates and Wendell Mayo. They allowed me to be contrary in the best way.

Thank you to the friends who have constantly encouraged and believed in me, including Allison Pavolko, Stacy Malena, Elizabeth Fogle, Sharon Gallagher, and Celise Schneider-Rickrode. Thank you to Mara Taylor for being the very best writing partner and for keeping me focused. Thank you to my very talented writing group—Joshua Shaw, Evan Ringle, George Looney, and Tom Noyes—for their feedback and support. Thank you especially to George Looney and Tom Noyes for guiding me through this process of becoming a writer for so many years.

Thank you to my parents, Rick and Theresa, who have believed in me since I first started writing stories in my notebook so long ago. Thank you to my sister, Erica, for listening to me talk about those stories.

And finally, thank you to Kevin for always being my first and best reader.

the sadness of spirits

Unnatural

I awoke this morning to find a dead salmon lying outside my bedroom window, its vacant black eyes rolled upward, reflecting the summer sun. This is the fifth such salmon I have encountered this week. I promptly removed it from my windowsill, wrapped it in newspaper, and put it in the freezer. I have never really known how to dispose of salmon, and so I stack them in my freezer, to be dealt with another day.

I brew a pot of coffee and consider this influx of dead fish. I find them everywhere: in my car, on my doorstep, inside my closet, tucked in my shoes. I am neither a fisherman nor an ocean dweller. There is no reason for these salmon to invade my house; I did not invite them.

I look for a river, a stream, a series of puddles a salmon can jump through, but I find nothing.

The children sit on a fluffy carpet in front of the TV, mesmerized by the were-man in the swamp. I don’t know why the other preschool teachers insist on showing the children this movie; it will certainly give them nightmares. I like seeing the kids quiet, though. It gives me a chance to study them, to imagine their futures, the people they will become.

There is one girl in particular who reminds me of myself when I was young—or at least the way I like to remember myself. Her hair is dark and wavy, her eyes curious and green. She follows directions with enthusiasm and giggles over macaroni creatures and the boys’ endless antics. I watch her as she watches the were-man—the tense tilt of her head as she follows his motions—and remember when I was young, innocently watching TV, doing whatever my teachers told me to do, packed into a small room with other kids whom I would never choose to befriend in another ten to twenty years. When I look at this image of my other, younger self, it is hard to see the resemblances between the child and the woman I have become.

I sigh and open my desk drawer to find a tissue. I find myself face-to-face with a salmon.

I once held hands with a man who worked in the seafood section of a grocery store. The scent of scallops and shrimp hung on his fingers. I imagined microscopic bits of scales caught under his nails, remnants of a life lived at sea.

I held hands with him again and then again. His eyes were murky. His voice lured me into something dark and oppressive. When I closed my eyes, I felt myself descending. I thought, This is what it means to drown. I found a man who wore expensive cologne and kissed him long and hard.

Salmon bodies appear in my bathtub as if lured by the prospect of an eventual bath. I scoop them out, carry them to my freezer. I am running out of room.

I have decided to seduce a sushi chef. My freezer is full, and I have no other options. I cruise past the sushi counter at the grocery store, batting my mascara-laden lashes, smiling in the chef’s general direction.

I walk by again and again until his eyes begin to follow me, then I make my move. I approach the counter, look into his eyes, and say, “I will take a tuna roll.”

“Tuna,” he repeats. “That’s a good choice.”

I smile and nod. “Yes, it is,” I say. “Indeed, it is.”

The were-man is on the move again. The children watch him with anxious eyes, flinching as he attacks various woodland creatures. I look at the other teachers, and they smile and nod. Clearly this is educational somehow.

I watch the dark-haired girl and wonder whom she will grow up to love. I imagine the wa

ys her life will be shaped and bent by others.

Sometimes I place myself in the position of this girl, frightened by the were-man, eager to go home and play video games or run around outside. Her life stretches before her, seemingly endless, punctuated by certain turning points: high school, college, marriage, a career. She doesn’t understand that these events are just small segments of her life. She doesn’t understand the vacancy in between, the endless day-to-day reality that needs to be confronted. She doesn’t see the details, the lines and color and clarity and flaws that real life presents. A plan is a plan, but plans often get changed. Directions alter. Others get in the way. Sense and order and logic can be smashed, disrupted, and overturned. Love is love, but love is also fear and trust and distrust. It is connection and disconnection, friendship and desertion.

For me, love was a man who woke up grumpy, calmed after coffee, laughed often, and never remembered to return phone calls. He turned the world upside down in a way that was beautifully devastating, uniquely wonderful. I held my breath when he told a joke, anticipating his amused smile more than the punch line. I held his hand while he watched TV, a book balanced in my other hand. I felt vulnerable in his presence, in a way that was both pleasant and terrifying. I ventured into him, the mystery that is another person, and he ventured into me, uncovering, exposing. It is possible to snap under such scrutiny, to cringe as your own flaws and secrets are recognized, one by one. It is possible to distrust and disconnect. This kind of intensity makes you consider the front door, the way the hinges always creak like the wail of the dead and opt instead for an open window as you make your escape one late spring night.

I couldn’t have known this when I was young, but life is hard and frightening. All of it, without exception, from beginning to end.

The sushi chef sits at my kitchen table eating a spicy stir-fry that I have spent the better part of the afternoon laboring over, finding the recipe, shopping for just the right ingredients. I watch as his face flushes from the hot peppers and the endorphins I imagine must be racing through his body. I make small talk and tell him jokes. I describe the preschool where I work, occasionally glancing nervously at the salmon that has appeared on my bookshelf. After dinner, I lead the sushi chef to my couch, put in a movie, and slowly edge closer and closer to him until we are sitting shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip. A few minutes later we are kissing, wrapped in an embrace that is strange simply because we are strangers. I think of the salmon stacked in my freezer, of the man who forgot to return phone calls, and it occurs to me that I shouldn’t be doing what I’m doing. I should feel guilt, shame, a strong sense of self-contempt, but instead I am vacuous. I am hollow. I am a shell. I am a woman who is running out of room in her freezer and has no other options.

A little while later, I lead the sushi chef back into the kitchen and make him a cup of coffee, dark roast, my specialty. While we are waiting for the coffee to brew, I casually open the freezer and offer him some salmon. “My brother loves to fish,” I lie. “And he’s always stocking my freezer. Why don’t you take some?”

The sushi chef smiles awkwardly and leaves with two, and only two, salmon. After he is gone, I take the rest of the coffee into the living room and recline on the couch. I study the salmon on the bookshelf, its pinkish red scales so similar to my own flushed skin, and imagine the way blood and veins flow scarlet and cross our bodies. There are so many colors that demonstrate life—green and red and brown and gold—but when I close my eyes and picture myself as I feel, I see only a scattering of gray.

I am at the bank, depositing a check, when I notice that the teller is wearing a wedding band. I casually let my eyes wander up to his face, verifying what I had only half noticed before. The teller appears to be very young, barely out of high school. His face is boyish and smooth; his blond hair is a mop of curls. He is at least fifteen years younger than me, but judging by his job, his dress shirt and tie and wedding ring, he is clearly more settled. I imagine him marrying his high school sweetheart, adopting a dog, having a child, embracing a career in the same town he lived in his whole life. I wonder if this is the way things are supposed to be. I wonder if there is something terribly wrong with me.

I am distracted when I reach into my purse for my checkbook and don’t notice the difference between scales and the smooth, lined cover of my checkbook. When I remove my hand, I am holding a salmon, its dull dead eyes staring helplessly at the teller. The teller gazes at the salmon and then slowly looks at me. “Is that natural?” he asks.

I shake my head, unsure. It occurs to me that I am a woman who breaks hearts and scares children; I don’t know what natural is. I think back on the events of my life and wonder if I have done everything wrong, taken all the wrong turns, made bad decision after bad decision. I don’t even know because I can’t see myself clearly. I feel my way through life from a blind place inside myself.

“I don’t think so,” I say finally. “But what can you do? They keep showing up.”

The teller shrugs and shakes his head. As I am leaving, I see him cast a sympathetic glance in my direction.

The sushi chef and I are lying in my bed. Somehow he has ended up with my pillow, and so I lay my head against his arm and try to ignore the discomfort. He turns to look at me and says, “I love you.”

I don’t know if he is in love with me, the intimacy we have shared, or the salmon I send home with him each time we meet, but really, I’m too tired to think about it. Instead I say the first words that come to mind, “Don’t love me. I can never love you.”

He turns to look at me, too dumbfounded to speak, and for a moment we lie together in silence. I wonder if I am the first woman to resist his declarations of love, to turn down an offer of romance in a world where everyone is looking for a soul mate. I expect him to roll out of bed and leave, maybe add a smart remark or two, but he only sighs and says, “Sometimes I can’t believe you work with children.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Random cruelty I can deal with, but a personal attack? I didn’t even think we knew each other well enough for that.

“You’re just so high-strung.” He strokes my hair like I’m a puppy or a beloved cat. “You need to relax a little. Have fun.”

I try to remember the last time I had fun, but all I can think of are the salmon that keep showing up around my house. On my windowsill. In my dishwasher. Under my bath towels. The salmon are wearing me out. I’m tired of wrapping them in newspaper, trying to think of ways to dispose of them.

“You know what I do when I’m stressed out?” he says. “I imagine that I’m in my favorite place. I close my eyes, breathe deeply, and try to remember all of the details. You have to think about what the place smells and sounds like. You have to make it as real as possible.”

“That’s nice,” I say. I can’t imagine ever taking the time to mentally transport myself to a “favorite place,” but I try to sound enthusiastic.

“Why don’t you try it now? Just lie back and imagine your place. I’ll do it, too.” And just like that his eyes are closed and he’s gone, breathing in and out, experiencing his happy place.

I stare up at the ceiling for a moment and then close my eyes. I’m not sure what my favorite place is. When I try to think of a favorite place, I draw a blank. When I think harder, I come up with a series of generic places—my grandma’s kitchen, my childhood backyard in winter, the mall—none of them places I am really attached to. I finally settle for a field, a meadow of sorts. I have been in a meadow only once or twice in my life, but it seems like a satisfactory favorite place, quiet, far away from people and salmon.

I imagine that I am standing in the center of the meadow.

I imagine that there is a slight breeze, making the tall grass wave like it is being stirred by a million tiny fingers. There are flowers, too, purple flowers. Purple is my favorite color. Flowers are some of my favorite objects. I stop to smell them in the grocery store.

I try to imagine myself breathing in and breathing ou

t, but I can’t. My chest feels tight, constricted. I gasp for air, but nothing comes. I am standing in open air, and I am drowning. On the ground before me is a salmon, its mouth opening and closing easily. I open my eyes with a start, relieved to be back in the bedroom.

The sushi chef turns to look at me. “Are you okay?”

I nod, unable to speak. He continues to watch me, his eyes dark and worried. “Most people don’t react that way to their favorite place,” he says. “What were you thinking about?”

“Nothing,” I say. “I’m fine.” I feel dissected by his gaze, my actions turned over and prodded, and I look away. He runs his hand along my arm, waiting for me to speak, and I feel a shiver of longing, cold and frightening in its need. When he leaves later that night, I will stretch myself across the bed, taking all the space for myself. I will stop returning his phone calls. I will erase him from my mind. For now, I fix my attention on the far wall and shrug off his questions.

The salmon will continue to appear, in plant holders and under pillows, a migration running directly through my house, crowding my space.

When the were-man devours a rabbit, bones snapping and cracking, several of the children reach their breaking point. There are gasps, sobs. The dark-haired girl gets up and tries to run out of the room, crying, and I am the first to intercept her. I get down on one knee, bringing myself to her level, and try to envelop her in a hug. A hug seems reasonable to me, especially after the sight of such a brutal and untimely death, but she pulls away, runs to another teacher who has come up behind me. As the other teacher comforts her, the dark-haired girl gives me a funny look from beneath her tears. “You smell,” she tells me. “Like fish.”

I take the were-man movie home with me and watch it once, twice, studying the furry man in the swamp, hunched and filthy, preying on small defenseless creatures. As I watch, I wonder who the man was before he became the were-man in the swamp. Was he married? Did he have children, a job, responsibilities? Or was he someone who always hovered on the edge of humanity, unable to connect, waiting for that one bad day that would send him running into the wilderness?

The Sadness of Spirits

The Sadness of Spirits